Metacognitive Self-Reflection: What? Why? How?

Metacognition is typically referred to as “thinking about thinking” or “thinking about learning.”

Metacognition refers to people’s abilities to predict their performances on various tasks… and to monitor their current levels of mastery and understanding… Teaching practices congruent with a metacognitive approach to learning include those that focus on sense-making, self-assessment, and reflection on what worked and what needs improving. These practices have been shown to increase the degree to which students transfer their learning to new settings and events. (National Research Council, 2000)

Metacognitive self-reflection is a kind of critical reflection in which students:

- describe their own learning process,

- monitor their own learning strategies and attitudes, and

- manage or even adjust those strategies and attitudes.

Other kinds of critical reflection may question the content, concepts, or activities of learning, knowledge, or science, but metacognitive self-reflection exercises highlight one’s own relationship to these. In that way, metacognitive reflection supports other kinds of critical reflection. This means that students are invited to consider which content or activities helped them learn, how they ‘made sense’ of what they were learning, and the obstacles and emotions they encountered. When self-reflective activities are encouraged throughout or highlighted within a course, students may build on or improve their metacognitive skills. Studies have suggested this positive outcome even for intellectually or emotionally challenging topics like racism (Chick et al., 2009).

Teachers can encourage development of metacognitive skills to help train more self-directed, self-aware learners who are better able to transfer their learning to new topics and endeavors.

Metacognitive reflection should be authentically related to the content and contexts of the material and experiences in the course. This way, it can support varied learning objectives and competences, through encouraging students to acknowledge and articulate their learning and thinking –their strengths and their challenges.

Overall, metacognitive reflection is often overlapping with other kinds of critical reflection including the “reflective observation” and “abstract conceptualization” in Kolb’s Learning Cycle, “bridge building” in Co-constructed Developmental Teaching Theory and “examining experience” in the DEAL model of reflection. For Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) revised Bloom’s taxonomy, “metacognitive” is the most abstract type of knowledge in learning. Within this type of knowledge are the sub-types of: 1) strategic knowledge, 2) knowledge about cognitive tasks (including appropriate contextual and conditional knowledge) and 3) self-knowledge. In Marzano and Kendall’s (2007) taxonomy, metacognition is an entire category of educational objectives.

No matter the model of learning, metacognition and reflection are thus an integral phase to consider. By explicitly and intentionally giving space for metacognitive self-reflection in university classrooms, instructors can better support lifelong, transferable learning, in all course types and for all disciplines.

Types of Courses

While the following learning objectives are neither exhaustive nor comprehensive for the types of courses listed, they are a starting point for thinking about how to productively integrate metacognitive reflection into your courses:

Different Fields

While this technique is probably most frequently employed in the humanities and social sciences, metacognitive self-reflection can be useful for students studying any subject, including mathematics and hard sciences. The literature on teaching and learning is rich with examples of how metacognitive skills can be built in courses from varied subjects such as biology (Tanner, 2012), philosophy (Concepción, 2004), and many more (e.g. psychology, literature and geography in Chick et al., 2009).

See the Metacognitive Self-Reflection Annotated Bibliography for the above resources and others.

Fostering Self-directed Learners

One of the most valuable competences is that metacognitive strategies help students to become self-directed learners (Ambrose et al., 2010). For those of us who believe that much of the specific information that students learn at university will likely fade, the most important learning outcome we can encourage in students is ‘learning to learn.’ Thus, when faced with new contexts, changing labor markets, and everything else we cannot predict, our students will be critical, adaptable, and up to the challenge.

Resources: What do you need to implement it?

You need only the time and the willingness to become familiar with the principles of metacognitive self-reflection and to make space for the activities in your classroom and courses.

A strength of this student-centered classroom technique is that there are comparatively few barriers to implementing these practices, some of which you probably have already heard of or may already be using in your courses to some extent.

Principles: How can we do metacognitive self-reflection well?

We have all been asked to reflect on anything from the completion of our higher degrees to the customer service experience with a company. Students have probably encountered self-reflection exercises by the time they reach you, some of which were likely thoughtlessly designed –the chief offenders being standardized course evaluations and one-time retrospective reflections on a project or paper.

So, how can we design our exercises and our courses to actually train and encourage students to practice metacognitive self-reflection? I’ve curated some principles and techniques for you as a reference guide, gleaned from a literature review and my own experiences with employing these techniques in the classroom. I would love to hear what else you think is important, and which successes and challenges you’ve had in your own classroom.

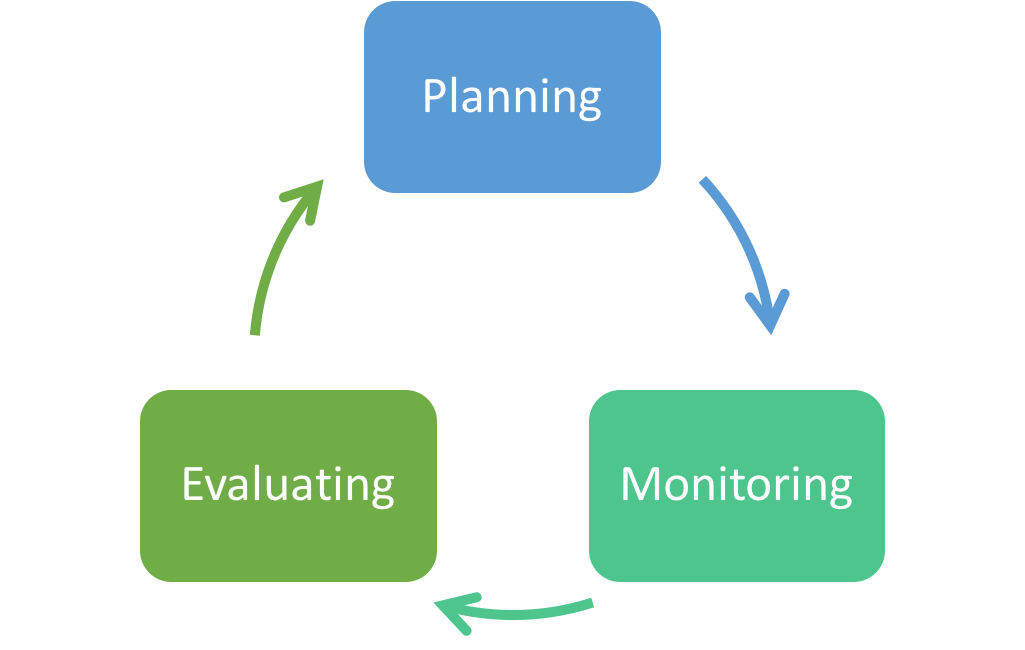

Teachers can avoid the pitfall of only thinking about self-reflection once the project/learning is over by incorporating activities or space for metacognition at each phase of learning or thinking. Consider how you could incorporate self-reflection at each of the three phases: planning, monitoring, and evaluating.

Planning

- Takes place before or at the start of a process or activity

- Involves looking to the future

- Also helps to think about what one already knows or assumes about the topic or activity and also about their own metacognitive knowledge (self-assessment)

Monitoring

- Takes place during or in the midst of a process or activity

- Involves looking inward

- Helps identify challenges as well as productive practices

- Allows for possible adjustments

Evaluating/retrospection

- Takes place near the end or after a process or activity

- Involves looking backwards

- Phase of synthesizing and making sense of one's learning

Please see this resource from the University of Michigan Sweetland Center for Writing for activities based on the metacognitive cycle of planning, monitoring, evaluating.

We should aim to design exercises that are most likely to facilitate the kind of self-reflection that will improve students’ metacognitive skills and to avoid the trap of the one-off retrospective reflection that is unlikely to inspire depth from students. In a nutshell, we should not assume that students have developed metacognitive skills, any experience with expressing metacognitive reflection, or that this is an intuitive kind of knowledge or thinking.

- Students might not be familiar or comfortable with this way of thinking.

- They may not have the skills to express the metacognitive knowledge that they do have.

- They may not feel comfortable sharing these kinds of thoughts or ideas with others.

Some ideas for scaffolding metacognitive skills include:

- Incorporating a plan for several and various low stakes reflective exercises throughout the semester. A diary works well for this.

- Explain the logic behind metacognitive self-reflection and remind students about the goal of these exercises regularly.

- Respond directly and specifically to students' reflections, especially to earlier exercises. You may want to encourage elaboration or ask questions to direct students towards reflecting on how they think or learn.

Other than training or scaffolding metacognitive skills and self-reflection activities, you can design them using techniques to encourage deeper reflection. By aiming to encourage reflection that is authentic, social, and responsive, the students may derive the most benefit from these activities (Sweetland Center for Writing, 2020). Authentic reflection means students are thinking about a real problem or question that they are facing, perhaps even while they are addressing it (as opposed to after a project is completed). Social reflection may take the form of ‘think alouds’ where students speak to a partner for a few minutes without being interrupted (then switch to listen for a few minutes without interrupting their partner). This allows students to perhaps reflect more authentically since they are speaking to a peer instead of writing to a teacher. It also allows them to hear the metacognitive reflection of another student; they may be exposed to a diversity of thinking and learning strategies.

Furthermore, classwork is typically biased towards written reflection, while some students may find other forms of reflection (art, music, movement, etc.) more meaningful or authentic (Harvey et al., 2016). If you can make room for alternative forms of reflection in your course, you may open up space for deeper, more authentic reflection.

- Authentic

- Should relate to what students are actually learning, should be specific

- Should be relevant to the field or to the task

- Social

- Helps encourage a culture of metacognitive expression

- Reveals that experiences/thinking/learning can be different between people

- Responsive

- Write or provide other responses to students’ reflections, posing questions or suggesting ideas

- Keeps students reflecting metacognitively throughout the semester

- Also helps students find solutions to issues or affirmation of productive practices

- Remaining open to different forms of reflection

- Creative reflection

- Moving away from only writing

To encourage authentic metacognitive self-reflection, teachers should aim to cultivate a metacognitive environment in their classroom throughout the course. A few additional ideas for creating this environment include:

- Training or scaffolding [see above]

- Be open to other (including creative) forms of self-reflection [see "Encouraging authentic self-reflection" above]

- Regularly incorporating short, low stakes metacognitive activities into your classroom like “Classroom Assessment Tools – CATS”

- Modeling and practicing metacognitive self-reflection as a teacher

Key source: faculty metacognition (Tanner, 2012, p. 118-120)

Contexts: What do I need to take into account when implementing this technique?

- Classroom size, class length

- Will you have time to implement these exercises in class?

- How many of them will you be able to read or listen to? Will you respond individually to students’ responses? Will you summarize student responses in class?

- Teacher workload

- To what extent will you be able to provide responses or feedback to student metacognitive reflective exercises?

- Will you assess students’ responses in some way?

- A plan for the entire course is the best way to scaffold and support building metacognitive skills in students.

Next Steps

Do you still have questions about how metacognitive self-reflection might be useful to your students or how it may be implemented in your classroom?

Check out the Metacognitive Self-Reflection FAQ or the Metacognitive Self-Reflection Annotated Bibliography.

Ready to plan the reflective assignments or prompts for your course?

The page on Planning and Assessing Metacognitive Self-Reflection in Courses contains a course plan and sample prompts for inspiration!

Would you like to introduce and/or further explore this technique with your colleagues?

See this Metacognitive Self-reflection Teacher Workshop Kit and start the conversation!

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., and Norman M. K. (2010) How Learning Works : Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition). New York: Longman.

Chick, N. L., Karis, T., and Kernahan, C. (2009) Learning from Their Own Learning: How Metacognitive and Metaaffective Reflections Enhance Learning in Race-Related Courses. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 3(1),1-28. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030116

Concepción, D. W. (2004) Reading Philosophy with Background Knowledge and Metacognition. Teaching Philosophy 24(4), 351-368. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil200427443

Harvey, M., Walkerden, G., Semple, A., McLachlan, K., Lloyd, K., and Baker, M. (2016) A song and a dance: Being inclusive and creative in practicing and documenting reflection for learning. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice. 13(2), 3. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1101273.pdf

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L. & Cocking, R. R., (Eds.). (2000) How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school ( Expanded Edition). Washington, D.C.: National AcademyPress. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/9853/how-people-learn-brain-mind-experience-and-school-expanded-edition

Sweetland Center for Writing. (2020). Cultivating Reflection and Metacognition. University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/instructors/teaching-resources/cultivating-reflection-and-metacognition.html

Tanner, K. D. (2012) Promoting Student Metacognition. CBE-Life Science Education. 11,113–120. https://www.lifescied.org/doi/pdf/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033

University of Puget Sound Website (2020) Creating Critical Reflection Assignments: Design Models. https://www.pugetsound.edu/academics/experiential/for-faculty/available-resources/creating-critical-reflection-assignments/design-models/